The following blog was contributed by Wiley Blevins, an author and phonics specialist living in New York City. Mr. Blevins holds an M.Ed. from Harvard University.

Recently, a national conversation in schools and the media has emerged around how we best teach our young learners to read. This conversation has been couched under the umbrella of the Science of Reading. We certainly have a large body of ever-evolving information about how to teach children to read. This information comes from educational researchers, cognitive scientists who do brain research, linguists, school practitioners like yourself, and so on. Unfortunately, some of this knowledge—especially that from outside of education (e.g., brain researchers)—is largely unknown by classroom teachers and not applied to many of our most commonly used reading programs. As a result, districts around the country have begun reexamining the materials they use to teach children to read to ensure these materials are aligned to this body of knowledge.

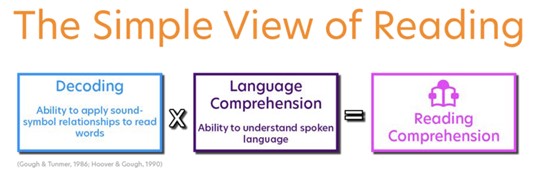

Two older established models of reading have emerged during this national examination of our early reading curriculum: the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope. The Simple View of Reading (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) states that reading comprehension is a product of decoding (e.g., phonics) and language comprehension (e.g., vocabulary and content knowledge).

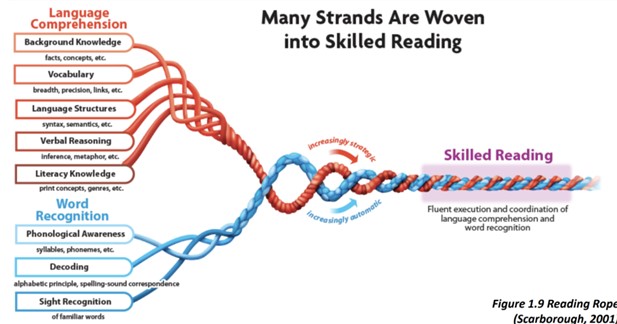

Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) fine-tuned this model to specify aspects of each area of reading instruction and how they intersect. As a student’s decoding skills become more automatic and they become more strategic in using their growing language comprehension skills, these skills intertwine. The result: students develop into skilled, fluent readers.

In these models, the decoding piece includes foundational skills like phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, concepts of print, and phonics. So how do we align our phonics instruction to the Science of Reading? There are four important guideposts to consider.

Guidepost 1: Scope and Sequence

In order to effectively teach phonics, we need a clearly defined scope and sequence. This is a scope and sequence that goes from easier to more complex skills. Confusing letters and sounds are separated, and so on. This scope and sequence provide the spine on which all of the instruction rests. It is a roadmap for teachers. What to teach. When to teach. And how much focus to give each of these skills.

But having a scope and sequence isn’t enough. A scope and sequence must be more than a list of skills that you march through in an exposure-focused way. In order for a scope and sequence to be impactful, it must also have a built-in review and repetition cycle. Once we introduce a new skill, for most of our students, it takes a significant amount of time to get to mastery. Students have to get to mastery so that they can transfer those skills to all reading and writing situations. So after a skill is introduced, it should be reviewed, applied, and assessed for at least the next four to six weeks.

Guidepost 2: Systematic and Explicit Instruction

Phonics instruction needs to be systematic and explicit. Systematic is related to having a scope and sequence and teaching those skills as a system. But teaching phonics as a system means that we go beyond skill-and-drill practice. We must also have robust conversations with our students about how that system works. So great phonics instruction is active, engaging, and thought-provoking, whereby children are observing and talking about how words work. Activities such as word building and word sorts (with follow-up question prompts like “what did you learn about these spelling patterns?”) aid in these conversations.

Explicit refers to the initial introduction of a phonics skill. Teachers need to explicitly state the sound-spelling connection (e.g., the /s/ sound is represented by the letter s). In an explicit introduction to the skill, the teacher models how to sound out words with the new skill and then gives children guided practice opportunities to apply the skill in isolated words and in connected text. This avoids the pitfalls of discovery learning, which require students to possess prerequisite skills that some may not have.

Guidepost 3: Daily Application to Reading and Writing

Daily application to reading and writing during the phonics lesson is critical. It is in the application where the learning sticks. This requires students to read, reread, talk about, and write about decodable (accountable) texts in which they can apply their newly acquired phonics skills to get to mastery faster. These texts have a high percentage of words that can be sounded out based on the phonics skills children have learned, as well as some irregular high-frequency words and the occasional story word to make more engaging reads.

The most impactful instruction has students not only read and discuss these stories but write about them as a follow-up. If it’s a fiction story, students can write a retelling. If it’s an informational piece, students can create a list of facts learned. This requires students to apply their growing reading skills to writing immediately. The book can serve as a useful and supportive scaffold.

Guidepost 4: Assessment

Assessment needs to inform instruction. When it comes to phonics, assessments must be viewed through two lenses: accuracy and automaticity. This tells us if students have knowledge about what has been taught (accuracy) and if they have acquired fluency with those skills (automaticity).

Phonics instruction requires two critical types of assessments: comprehensive and cumulative. A comprehensive phonics assessment is a survey of all the skills a student would learn in a phonics continuum (from identifying letter-sounds to reading words with short vowels, long vowels, complex vowels, and finally multisyllabic words). This assessment is essential at the beginning of a school year to identify which students have not mastered previous grade-level skills, which are meeting grade-level expectations, and which are beyond the scope of skills covered in a grade.

A cumulative assessment is what’s missing from most instruction and is critical for phonics success. A cumulative assessment assesses the new target skill and previously taught skills (generally looking back 4–6 weeks). This assessment monitors skill growth over time—a more accurate assessment since it takes weeks for most students to get to mastery on a taught skill. It can also alert a teacher to decayed learning (skills in which not enough review and application has been provided and the skill has “slipped away”) so that course corrections can be made to avoid potential and serious learning issues as students move from grade to grade. In addition to these assessments, teachers need to regularly listen to students read aloud and evaluate their writing for evidence of transfer.

These four guideposts alert us to key aspects of phonics instruction that need to be in place, how to teach them (see the 7 Characteristics of Strong Phonics Instruction link), and how to assess them. Evaluating our phonics curriculum against these guideposts can strengthen our instruction and maximize student learning.

Resources

7 Characteristics of Strong Phonics Instruction eBook

Meeting the Challenges of Early Literacy Phonics Instruction Leadership Literacy Brief

Selected References

Blevins, W. (2021). Choosing and using decodable texts. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Blevins, W. (2020). Meaningful phonics and word study: Lesson fix-ups for impactful teaching. New Rochelle, NY: Benchmark Education.

Blevins, W. (2019). Meeting the challenges of early literacy phonics instruction. Literacy Leadership Brief No. 9452. International Literacy Association.

Blevins, W. (2016). A fresh look at phonics: Common causes of failure and 7 ingredients for success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Blevins, W. (2017). Phonics from A to Z: A practical guide. 3rd Edition. New York, NY: Scholastic.