The following blog was contributed by Betsy Okello, Ph.D, Assistant Professor, The Mary Ann Remick Leadership Program, University of Notre Dame.

As Catholic school educators and leaders, committing to cultural responsiveness is not merely nice to do or an add on to our core curricula. It is essential to developing our students spiritually, academically, and socially. The first step on the journey to becoming culturally responsive educators is to clearly understand what this commitment means in terms of our practice and our habits. What does it mean to be responsive, not just to our students’ cultures but also to the diversity of cultures in our global community? Here, we will focus on what cultural responsiveness is and what it is not.

Cultural responsiveness is providing students with windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. Cultural responsiveness is not using a simple checklist to match the current students in my class to the books on my library shelf. In the 1990s, Rudine Sims Bishop challenged educators to provide students with windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors through books and images. This metaphor is widely cited in educational circles but needs to be deeply understood rather than taken at face value. Providing students with windows through books allows them to encounter people who have different experiences, ways of dressing, ways of speaking, and cultural traditionsand to find value in these differences. These stories should highlight the diversity among ethnicities and nationalities so that students understand that not all Latinx families are Mexican, and not all Asian families are Chinese. There is diversity both within and among these communities. Providing students with mirrors allows them to see their own experience reflected in the stories they read in school. This is critical both for students’ development as readers and their own sense of dignity and worth. We know from research that children can comprehend texts more deeply when those texts include characters and topics that match their cultural background knowledge (Bell and Clark, 1998). We want our students to be able to do more than just decode words. We want them to be able to make meaning, connections, and use what they learn through texts. Reading books that activate the background knowledge of all students allows them to find value in the knowledge they bring into our classrooms (their language, heritage, cultural traditions, etc.). Providing students with sliding glass doors allows them to step inside the experience of another. We have seen students do this countless times as they enter the fantasy worlds of Hogwarts, the Magic Tree House, or The Shire. These imaginative worlds are magical and important but so too is reality. We can also invite students into a city bus ride to the last stop on Market Street, a forest of freshly planted trees in Kenya or an after school drawing lesson between a grandfather and grandson. These stories, settings, and characters matter and reading them in our classrooms will show students that their stories, experiences, and families matter as well.

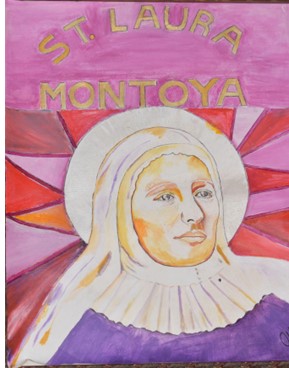

Cultural responsiveness is something we do all the time. Cultural responsiveness is not reserved for holidays or particular celebrations. Annual, month-long celebrations such as Hispanic Heritage Month and Black History Month are important because they establish dedicated time to highlight the cultures, traditions, and contributions of these communities. Setting aside an entire month can help ensure that we pay particular attention to the diversity within each community. These celebrations provide a wonderful opportunity to highlight books written by authors of color (see this video on Hispanic Heritage Month and this one on Black History Month for some suggested titles). However, this cannot be the only time students encounter the stories, perspectives, and images. Cultural responsiveness is not something we only pay attention to when prompted by the calendar. Cultural responsiveness needs to be something we commit to daily – across subjects and throughout our day. Even when our youngest students are beginning to read, teachers can use decodable texts that are interesting, culturally responsive, and relevant to their daily lives and experiences. Students can read informational text on topics related to social justice that are accessible for their developmental and reading levels. And especially in our Catholic schools, students can learn the stories of diverse saints throughout the year so that they can come to know saints who look like them. Becoming more culturally responsive requires us to make deep rather than surface level changes to our curricula. These changes can even be co-constructed along with students. Such design work alongside students helps guard against superficial curricular changes (such as changing the names of characters or the settings) rather than centering and valuing the knowledge that students bring that is absent from the current curriculum. When making changes to our practice and habits to become more culturally responsive, we must consider all three aspects of culturally relevant pedagogy: academic achievement, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness(Ladson-Billings, 1995). We can ask ourselves, will this help our students better access and understand the content? Will this help students become more fluent in their own culture and the culture of another? And will this help students develop a sociopolitical conscience so they can make better decisions and choices as Catholics committed to Catholic Social Teaching and as global citizens?

Cultural responsiveness is a commitment we make to families and communities. Cultural responsiveness is not just about what happens in our classrooms and schools. When students enter our classrooms, we want them to be able to bring their full selves across the threshold and to be able to recognize and draw upon the funds of knowledge they bring. We also want students to go back out of our classrooms with new knowledge that they use to navigate the worlds they inhabit outside of our classroom walls. To be responsive to students’ cultures, we must bring an asset lens and orientation to understanding the richness and diversity of experience they and their families bring and interrogate how we as Catholic school educators can more powerfully understand and engage that richness. In our Catholic schools, we do not just teach students how to do certain subjects, such as how to solve problems in math, how to read, or how to do a science experiment. We understand education as the formation of a scholarly identity. How can we teach students to become mathematicians, readers, writers, artists, scientists, and saints? What schools teach, and what kinds of texts, stories, examples, and problems teachers share with students, influences what students think is possible and what they can imagine. Providing students with access to a wide range of high quality culturally relevant texts expands their vision – both their ability to see themselves in new ways and to empathize with others. As Catholic educators, we honor parents as the primary educators of their children. This requires that we build and sustain relationships with families and are responsive to their cultures and needs as well as to the cultures and needs of our students. This might look like inviting families in as guest readers in our classrooms. It might look like making home visits to better understand students’ home lives. It might look like hosting family literacy and math nights to better support families. Engaging in these activities with students and families celebrates, honors, and draws upon their expertise and gifts and helps us understand and meet the needs of all members of our communities.

As we begin the celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, let us take the opportunity to commit or re-commit to cultural responsiveness as Catholic school educators. Let us take this journey together recognizing the importance of multiple perspectives and the power of community. Let us challenge ourselves to consider how the doors of our classrooms and schools open both ways: How can we think about the ways the doors of our classrooms and schools open in and invite students and families into this space? What experiences do they have inside the space? What knowledge do they create? And how can that knowledge and experience transcend the doors back out into communities to transform them and ourselves?